Criminal Law Update: Summer 2018

Introduction

Last month, the Supreme Court of the United States issued a monumental, long-awaited decision on privacy rights, Fourth Amendment, and digital data. In United States v. Carpenter, the Court ruled that to access an individual’s historical cell phone data, law enforcement needs a warrant supported by probable cause. This applies to the “396 million cell phone service account” in the U.S., as identified by the Court. To hear the figure is overwhelming – 396 million cell phone accounts for a nation of 326 million! The 5-4 split decision displayed the complexities of applying Fourth Amendment law to evolving and invasive technology which has become a natural part of American lives.

What is Historical Cell Phone Data?

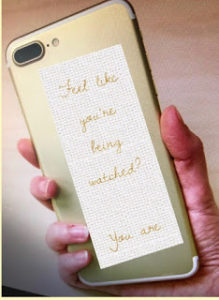

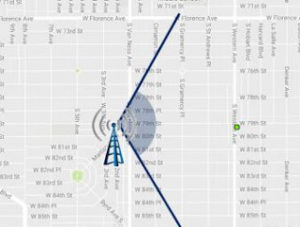

Cell phones operate by connecting to a set of radio antennas called “cell sites” which are typically mounted on towers. These cell sites have directional antennas that divide the covered area into sectors (see figures below). The cell phones then scan the environment for the best signal. This does not have to be the closest signal, as I recently uncovered during a federal RICO trial when cross-examining a government’s cell site expert. However, for the most part, when a cell phone “pings” off of a given sector of a tower, the presumption is that the cell phone is within range of that particular tower.

Example of a carrier’s sector

When evaluating urban areas with small city blocks, the location can be more difficult to pin down, because as mentioned, the cell phone does not necessarily connect to the closest tower and it is not the same thing as a GPS. But when comparing areas with fewer towers (such as rural areas), or a location across counties or states, then of course, the location of a cell phone can be extremely useful and potentially incriminating.

Each time a phone connects to a cell site, it generates a time-stamped record called “cell-site location information” or CSLI. Wireless carriers collect and store this CSLI for their own purposes, including for the purpose of improving their service. As one can imagine, law enforcement is keen to obtain CSLI as an investigative tool.

The Carpenter Decision

Which brings us to Carpenter. In April of 2011, four men were arrested in connection with a string of Radio Shack and T-Mobile armed robberies & lt that occurred over a two-year period in the Detroit area. One of the arrested individuals confessed and surrendered his phone to the FBI and provided the government with the phone numbers of the other conspirators (including Carpenter). The government proceeded to apply for court orders for the cell-site records associated with the numbers they were given.

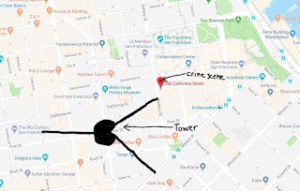

In accordance with the Stored Communications Act(SCA), a magistrate judge granted the FBI’s request to obtain “cell site information for the target telephones at call origination and at call termination for incoming and outgoing calls” from various wireless carriers. The order granted by the judge was not a warrant but did satisfy the requirements of the SCA. While a warrant requires probable cause, the SCA only requires “reasonable grounds to believe that the contents of a wire or electronic communication, or the records or other information sought, are relevant and material to an ongoing criminal investigation.” Using the historical cell-site records, the government presented evidence at trial that Carpenter’s cell phone was within a two-mile radius of four robberies. Carpenter was convicted by a jury and sentenced to over 100 years in federal prison.

Carpenter, with the backing of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), ppealed on the basis that the government’s seizure of his cell site records was a violation of the 4th Amendment. The Sixth Circuit affirmed his conviction, finding that Carpenter lacked a reasonable expectation of privacy in the location information because the cell user voluntary conveyed the cell-site data to the carrier.

The Supreme Court disagreed. The Court cited to its 2014 decision in Riley v. California, which held that police officers must generally obtain a warrant before searching the contents of a phone due to the “immense storage” capacity of modern cell phones. Taking a step further, the Court recognized that the sort of digital data at issue – personal location information maintained by a third party – did not fit neatly under existing precedents. In reaching its conclusion, the Court addressed two sets of cases involving privacy interests: a person’s expectation of privacy in (1) his physical location and movements and GPS tracking; and (2) information voluntarily turned over to third parties. The Court’s decision expanded upon these privacy interests and principles.

Individuals “have a reasonable expectation of privacy in the whole of their physical movements,” Justice Roberts wrote in the majority opinion.

The Court further recognized that CSLI is a completely new phenomenon, as the data at issue tracks a person’s past movements through cell phone signals. The information is “detailed, encyclopedic, and effortlessly complied.” And ultimately, the Court decided that just because the information is held by a third party (the carriers), it does not by itself “overcome the user’s claim to Fourth Amendment protection.” And although the records are generated for commercial purposes, the Court reasoned, that distinction doesn’t negate Carpenter’s anticipation of privacy in his physical location.

“As with GPS information, the time- stamped data provides an intimate window into a person’s life, revealing not only his particular movements, but through them his ‘familial, political, professional, religious, and sexual associations.’”

Justice Kennedy’s Dissent

In one of his last opinions on the bench, Justice Kennedy dissents, primarily on the third-party doctrine, declining to distinguish CSLI from other business records. Kennedy concludes that no search occurred, and that Carpenter lacked a privacy interest in the records, which were controlled by the third party wireless provider. Kennedy also describes instances in which a subpoena has been found to be sufficient to obtain a variety of records such as credit cards, vehicle registration records, hotel records and employment records as examples. Finally, Kennedy criticizes the majority opinion by emphasizing that CSLI is an important investigative tool that can be used to “apprehend some of the Nation’s most dangerous criminals.”

Conclusion

The Supreme Court thus held that (generally) will need a warrant supported by probable cause to access CSLI (leaving open the possibility of exceptions for exigency and the like).

Notably, Justice Sonia Sotomayor, who has been a champion of defending property rights and personal privacy, was thus arguably more sympathetic to Carpenter and she reminded the Court of the stakes in the case. “Although this case is only about the historical cell-site records, which indicate where a cellphone connected with a tower,” she stressed, “technology is now far more advanced than it was even a few years ago, when Carpenter was arrested. A provider could someday turn on my cellphone and listen to my conversations,” she said.

This case is a sobering reminder of the multitude of ways in which we risk our privacy rights every single day when we activate our smart phones. Many are starting to reconsider: is it worth it or are we took hooked? Or do we trust the Supreme Court to continue to advocate for and respect individual privacy ights?

Opinion delivered by: Roberts, Ginsburg, Breyer, Sotomayor, Kagan. Dissent by Thomas, Alito and Gorsuch and Kennedy.